A few weeks ago a group called Right To Equality launched a campaign to change the law to require “affirmative” sexual consent—actively saying yes to sex rather than just not saying no—which was immediately derailed by a row about language. The problem was the same one Northwest Cancer Research ran into last November, when it tried to promote cervical cancer screening with a billboard featuring crossed female legs alongside the rape-myth-inspired strapline “Don’t keep ‘em crossed/ get screened instead”. Right to Equality’s ads alluded to another rape cliché: its “provocative” strapline, which appeared on posters over a close-up of a woman’s face (or alternatively on a T-shirt below the wearer’s face), was “I’m asking for it”.

This did not go down well. The Daily Mail‘ summed up the obvious problem in its headline “Sex abuse survivors blast… ‘insulting and triggering’, ‘I’m asking for it’ consent law campaign as they say, ‘This was what my rapist told me’”. And that wasn’t just the view from the Tory tabloids. An opinion piece in the Independent called it “the most offensive sexual assault campaign I’ve ever seen”, while a critical article in the New Statesman (aptly headed “No one asked for it”) judged it “troublingly misguided”.

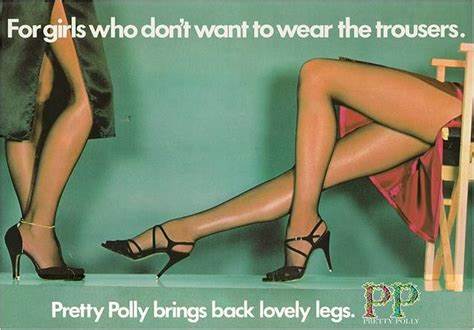

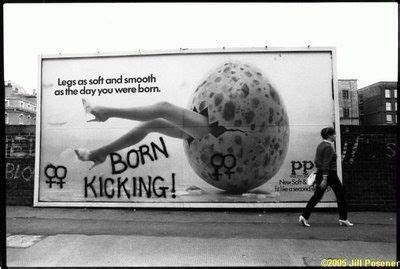

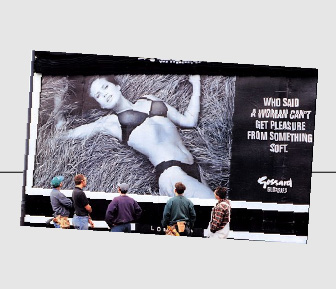

By now it should surely be clear that women do not, on the whole, appreciate sexualized imagery and verbal innuendo in messaging on subjects like rape and cancer. They might find it innocuous in other contexts (in an ad for Cadbury’s Flake, say), but in this context they find it tasteless and offensive. So why do the adwomen–and they are, almost always, women–keep giving us these “provocative” campaigns?

As I said in my post about “Don’t keep ‘em crossed”, I think a significant part of the problem is that ideas about how language works which are taken for granted in the creative industries often misfire under real-world conditions. To creatives it may seem obvious that provocative slogans are effective (attention-grabbing, memorable, etc.), but in the real world viewers may react to provocation in ways which undermine the advertisers’ aims. For instance, if a young woman goes out wearing the “I’m asking for it” T-shirt, will the people whose attention she grabs think, “oh, cool, she’s subverting a rape myth”, or will they think she’s saying she’s always up for it? Will they want to engage her in a conversation about consent, or will she become a target for catcalling and lewd remarks? The short answer is, it depends: both those reactions are possible. But if you assume you’ll only get the one you wanted, and don’t consider other possibilities, you may find yourself in the embarrassing position of running a feminist campaign about rape whose most vocal critics are rape survivors.

While there’s always potential for a message to be read in different ways by different people, that’s a particular issue with messages which don’t make their meaning immediately obvious, but instead present the viewer with a puzzle-solving task–a long-established tradition in British advertising, which often uses allusion and wordplay to give the viewer the satisfaction of working out what the ad is saying. “I’m asking for it” belongs to that tradition. To work out what its designers intended it to communicate, viewers need to recognize the strapline as an allusion to “she was asking for it”, realize that changing the subject pronoun to “I” implies that the woman in this version actively wants sex, and connect that to the text below the image (“let’s change the law to require a clear yes to sex”) to derive the solution that “it” doesn’t just mean “sex”, it also means “consent”, and that double meaning is the key to the message. Undeniably, this is clever. But is everyone who sees the ad going to get it?

The answer, I think, is “no”. Some viewers will miss the point simply because they haven’t engaged for long enough to work it out (eye-tracking studies have found that the average time spent looking at a poster ad is 1.7 seconds). Others, however, will miss it because they don’t share the background assumptions which are needed to get to the “right” answer. To read “I’m asking for it” in the way the designers intended–as a subversive twist on an old rape-myth–you have to recognize “women ask for it” as a myth. And research suggests that quite large numbers of people, especially people under 25, don’t think it’s a myth, they think it’s a fact.

To be fair, the campaign has taken criticism of “I’m asking for it” on board, and has now produced some new posters with less “provocative” straplines (e.g., “only yes means yes”). But understanding how language works in real-world situations isn’t just important when you’re designing publicity for a campaign about affirmative consent. Similar questions about how language works are also raised by the actual aim of the campaign, making affirmative consent a legal requirement.

Consent, of whatever kind, is obviously about communication, and that’s usually assumed to mean linguistic communication, which is thought to be less ambiguous, and so less open to (mis)interpretation, than other ways of signalling desire (e.g., through gaze, gesture or touch). What, after all, could be clearer and less ambiguous than the simple words “yes” and “no”? But as people who study everyday talk have been pointing out for years, in reality it isn’t that simple. The idea that if you want it you say yes and if you don’t you say no is at odds with what we know about how real speakers actually do things.

In 1999 the researchers Celia Kitzinger and Hannah Frith challenged what was then a ubiquitous piece of rape prevention advice–that if women didn’t want to have sex they should “just say no”–by pointing out that in reality it’s extremely rare for English-speakers to decline any kind of invitation or proposition by just saying no: most real-life refusals don’t even contain the word “no”. What people typically do is use a formula for refusal that involves some combination of hesitating, hedging, expressing polite regret and giving an acceptable, though not necessarily truthful, reason. For instance, if you don’t want to go for coffee with a co-worker you might say “um, I wish I could, but I really need to finish this report”.

Kitzinger and Frith presented evidence from focus groups that sexual propositions are not an exception to this rule: their female informants reported using the same refusal formula in sexual situations as in others (e.g., “[pause], I’m really tired and I’ve got an early start tomorrow, so I think I should probably just go home”). In their experience this was usually effective, and where it wasn’t, that was not because the man hadn’t understood it as a refusal, but because he wasn’t willing to accept a refusal. In those cases they said they’d be wary of using the word “no” because of its potential to make him angry and more aggressive. “Just say no”, Kitzinger and Frith concluded, is bad advice: it’s linguistically unnatural, unnecessarily blunt (since everyone understands the conventional formula), and in a tricky situation it may increase the risk of violence.

Saying yes isn’t as risky as saying no (since it will usually be what the other person wants to hear), but it raises the same question about how natural it is. Is it true that “only yes means yes”? Is continually asking for/giving permission to do things (kiss, touch, undress someone, penetrate them) a kind of verbal interaction people either do have, or could be persuaded to have, in reality—or is it an unrealistic and misguided thing to expect of them?

I can’t claim to have a definitive, evidence-based answer, because for obvious ethical reasons there isn’t much data to base one on. We really don’t know much about how people “naturally” talk during physical sexual encounters. There has been some research on chatrooms where people who can’t see or touch each other use language to construct erotic narratives, and there are some studies of the fictional dialogue which appears in representations of sex (e.g., pornography and romance fiction). But it’s not clear how much this research tells us about the kind of “ordinary” sex-talk that isn’t scripted or performed for an audience.

It’s possible that it tells us something, though, since in the absence of more direct instruction (watching other people have sex, or practising it under the guidance of an experienced tutor) many people use fictional representations as templates for their real-life sexual encounters. Recently, for instance, there’s been concern about the extent to which young people are getting their templates from porn, a genre in which “consent talk” (i.e., explicit, ongoing verbal negotiation of what the parties do or don’t want) is not typically part of the script. Consent talk is also largely absent in representations where sex occurs in the context of romantic love. In romantic sex scenes what’s usually depicted is a quasi-mystical connection between two lovers which ensures that their desires are perfectly in sync: they don’t need to talk, their bodies just know. But if it isn’t modelled in the representations people use as sources of information and inspiration, how do they learn to do consent talk in real life? Is talking about it simple and straightforward, or is it something a lot of people struggle with?

In 1990 this became a real and consequential question for students at Antioch College, a small and “progressive” liberal arts college in Ohio, when the college introduced a new sexual consent policy as part of its disciplinary code (meaning that any student found in violation would face sanctions that included expulsion). The policy stated that consent had to be both affirmative and ongoing–explicitly sought and received for each discrete sexual act (so, no assuming that one thing “naturally” leads to another). As a spokeswoman for the college explained this to the media,

If you want to take her blouse off, you have to ask. If you want to touch her breast, you have to ask. If you want to move your hand down to her genitals, you have to ask. If you want to put your finger inside her, you have to ask.

The reason the college was making statements to the media was that the policy had caused nationwide controversy. It had been seized on by critics of campus “political correctness” (a major talking-point in the early 1990s) who decried it as an authoritarian attempt to limit adolescents’ sexual freedom– though at the same time they said the attempt was bound to fail, because no normal adolescent would take any notice. In 1993 I went to Antioch to investigate what was happening. I interviewed a number of people about the policy (mostly students, but also the Dean who oversaw its operation) to find out how they felt about it, what difference they thought it had made and what following it (if they did follow it) involved in practice.

The students told me that while a lot of people they knew were not complying with the policy (and some were vocally opposed to it), there were also many who had embraced it positively. The main benefit everyone mentioned was making it easier to refuse unwanted sex without getting the pushback that had been common in the past. However, some students also said that being compelled to think so specifically about what they did or didn’t want, and then to verbalize those thoughts, had resulted in them having more pleasurable sex.

The Dean believed that the policy’s main value was educational. She was exasperated by the argument that college students didn’t need “sex lessons”: Americans, she told me, were in denial about the extent of young people’s ignorance. The workshops students had to attend when they arrived invariably revealed how little many of them knew, not just about consent but about sex itself. But the policy had not, she said, solved the problem of rape on campus, which in her view was still prevalent, and still significantly under-reported.

One student who had served as a “peer advocate” agreed with that assessment. The policy, she explained, was at odds with mainstream peer-group norms which put pressure on women to acquiesce to men’s demands, and to keep quiet about it if things went wrong. It was also a fairly common view that talking explicitly about sex-acts was embarrassing, unromantic and potentially damaging to a woman’s reputation (if she talks about it so freely, doesn’t that suggest she’s a bit of a slut?) The students who were most enthusiastic about the policy were feminists and other social justice types who had consciously rejected the mainstream heterosexual culture. At progressive Antioch those people were fairly numerous, but even there they were not a majority; on many campuses they would be a tiny minority.

What Antioch’s experiment shows, IMO, is that it takes more than a written policy, even one backed up by serious disciplinary sanctions, to shift the linguistic and behavioural norms which are deeply embedded in a community’s everyday life. Redefining consent on paper is the easy part: the hard part is bringing what happens on the ground into alignment with that redefinition. The same point applies even more strongly to a campaign which wants to shift a whole society’s norms by rewriting the relevant legislation. Even if Right to Equality succeeds in changing the legal definition of consent, on its own that’s unlikely to be the game-changer they seem to think.

Part of Antioch’s problem was that the very explicit consent talk the policy prescribed evidently didn’t come naturally to most students. Even if we bracket the ones who opposed the policy for political reasons, many others perceived it as embarrassing or weird (even the peer advocate quoted above said that when she first arrived she thought it was “stupid”), while for some it was a turn-off, in conflict with what they thought sex should ideally be like. To become embedded in everyday practice, this kind of talk may need to be not just recommended, or mandated, in the abstract, but concretely modelled–and not (or not only) in sex education lessons, which also tend to be perceived as embarrassing and unsexy, but in the kinds of sexual representations people seek out voluntarily.

But you might think that’s only marginally relevant to a discussion of Right to Equality’s campaign. Though their website suggests they do see championing affirmative consent as, in part, a cultural intervention, an attempt to promote “healthy and respectful relationships” by “highlight[ing] the importance of communication”, their primary aim is to change what happens when someone reports that they were raped. If affirmative consent becomes the legal standard, they argue, a man who, for whatever reason, didn’t explicitly request and receive a woman’s consent will have no excuse: he will no longer be able to argue in court that the complainant’s behaviour (she didn’t say no, she acted like she wanted it) gave him a “reasonable belief” that she consented. Will that not be a game-changer?

Unfortunately, I doubt it. However consent is defined in theory, in practice (as I said earlier in relation to advertising messages) people will still tend to interpret the evidence they’re presented with in a way that fits their own beliefs. If jurors in rape cases are still operating with the same beliefs as before, just changing the question they have to decide on from “did she say no?” to “did he ask and get a yes?” will not necessarily change the outcome. The facts will still often be disputed—the complainant will claim he didn’t ask, the defendant will swear he did—and there’s no reason to think it won’t still be the man whose account jurors prefer, thanks to the combined power of “himpathy” (the desire to give men the benefit of the doubt) and the still-pervasive belief that women “cry rape”.

But there’s another reason why I don’t see redefining consent as a game-changer. In the last few years the way the justice system deals with sexual violence has been the subject of quite intensive investigation (we’ve had a major Parliamentary inquiry and several expert reports), and what’s emerged is a consensus that the main obstacle to justice is not the way the law is written, but the failure of the system, which is both under-resourced and pervaded by misogyny, to enforce it. The scale of that problem would be difficult to overstate: as the Victims’ Commissioner Vera Baird said in 2020, what’s supposed to be one of the most serious offences in the book has instead been “effectively decriminalized”. When she made that observation only 1.5% of recorded rapes were resulting in a criminal charge; that figure has since risen, but only to a still-paltry 2.4%. And even the five in two hundred accused rapists who do get charged won’t all end up standing trial. Cases are now taking so long to get to court that large numbers of complainants are dropping out, and without their testimony the case collapses. In these circumstances it seems pointless to debate whether changing the legal definition of consent will increase the number of convictions. You can’t get a conviction without a trial, and you can’t have a trial without a charge.

What the present situation calls for is deeds, not words. Rather than campaigning to change what the law says, we should demand action to change what it does.