The photograph below, taken at Manchester Piccadilly station earlier this month, shows an installation commissioned by North West Cancer Research to encourage more women to get screened for cervical cancer. Which is, of course, a worthy goal; cervical cancer screening can save lives. But when I first saw this photo, what I mostly felt was rage. I was so angry, I immediately reposted it with a critical comment on Twitter/X. Evidently this struck a chord: within a couple of days my tweet had racked up 134K views and prompted numerous replies from other women who found the installation “awful”, “crass” and “disgusting”. In this post I’ll take a closer look at what the problem with it is—and why that problem is so common in women’s health campaigns.

The installation consists of five large display boards arranged in a line. Mounted on each of the middle three boards is a disembodied pair of crossed female legs. They’re like the legs you see on mannequins in the hosiery sections of department stores: long, slender, and carefully positioned for aesthetic effect. They begin at the top of the thigh and end in Barbie-style feet wearing high-heeled court shoes. They are “diverse” insofar as they represent a range of skin colours, but there is no diversity in relation to age, body-size or personal style. The imaginary woman these legs belong to is clearly young, slim, and conventionally feminine. On its own the visual element of the display could easily be mistaken for a lingerie ad: it’s far from obvious what legs have to do with cervical cancer. But the connection is spelled out in the verbal message, which is split between the two outer display boards. Both parts address the viewer directly and in the imperative: on the left, “don’t keep ‘em crossed”, and on the right, “get screened instead”.

While there are many things to object to about this installation, the thing I found so shocking that it rendered me temporarily speechless was that injunction “don’t keep ’em crossed”. It’s offensive because the crossing and uncrossing of a woman’s legs is a well-worn metaphor for sexual continence or incontinence. That’s the real reason why girls are taught that it’s “ladylike” to sit with your legs crossed (and “unladylike” to sit with them apart): while this is often presented as a matter of aesthetics or good taste, what it’s really about is modesty, in the sense of chastity. By adopting a posture that completely conceals her genital area, a woman signals that she is not available for sex.

The flipside, of course, is that the uncrossing of a woman’s legs becomes a sign that she is open to sexual propositions. When I was growing up in the 1970s people often said, about both rape and unwanted pregnancy, that all a woman had to do to prevent it was “keep her legs crossed”. This was a commonplace form of victim-blaming and slut-shaming, but it also had a flipside which might be called “prude-shaming”. The woman who did “keep ’em crossed” could be accused of denying men access because she was “uptight”, frigid and sexually repressed. Which is also what “don’t keep ‘em crossed/get screened instead” implies—that it’s uptightness that stops women from getting screened.

This sexualization of a medical procedure is offensive in its own right, but if the aim is to increase the uptake of screening it also seems strategically ill-conceived. If women are really deterred from getting smears by a prudish reluctance to open their legs, then surely it would make more sense to try to take sex out of the equation, and talk about smear tests in the same way you’d talk about any other medical procedure involving the probing of a bodily orifice. These are, after all, quite numerous: if sexual references are not a staple feature of campaigns encouraging men to get their prostates checked, why should they have any place in campaigns about cervical cancer?

I say “campaigns”, plural, because the NHS and cancer charities have form for this. In 2021 the health app myGP ran a bizarre online campaign suggesting young women could remind their social media followers about the importance of regular smear tests by posting a picture of the type of cat (long-haired, short-haired or hairless) that best represented the current state of their pubic hair. The cat, obviously, was code for the explicitly sexualized term “pussy”. And it’s not just cervical cancer that gets this treatment. One Twitter commenter reminded me that in 2020 the Sun newspaper, which for several decades was famous for featuring a daily topless pin-up photo on page 3, ran a campaign to encourage breast self-examination whose title and slogan was “CoppaFeel!”. And in Canada a campaign to raise awareness of ovarian cancer renamed women’s ovaries “ladyballs”: its slogan was “have the ladyballs to do something about it”.

These campaigns persistently use the register of laddish banter, sometimes in combination with the visual language of pornography, in which women are reduced to their component body-parts (and often, as in this case, shown without faces, the most individualizing and emotionally expressive parts of the human body). It’s as if the designers are incapable of viewing female bodies from anything but a heterosexual male perspective, or of talking about diseases that affect thousands of women (some of whom will die from them) in anything but a laddishly jokey way. Does that not suggest an extraordinary level of obtuseness about, or indeed contempt for, women’s own experiences and feelings?

But if you’re assuming that the “don’t keep ‘em crossed” campaign must have been developed by men, I regret to tell you that you’re mistaken. The PR agency North West Cancer Research used, Influential, is led by women; a report on the website of Prolific North, a hub for digital and media professionals in the north of England, makes clear that women dreamed up those disembodied legs and came up with that repulsively rapey strapline. What were they thinking? Karen Swan, a director at Influential, explained to Prolific North that

We wanted a campaign that was playful and a bit cheeky in order to grab our audience’s attention, so the strapline “Don’t keep ‘em crossed” was perfect.

Cara Newton, head of marketing at North West Cancer Research, agreed, saying they’d wanted a campaign whose launch would create what she described as a “real moment”.

When I first saw the installation I did have a “real moment”, of the Proustian variety: it transported me straight back to my teenage years in the 1970s, when “playful and cheeky” sexism was ubiquitous in popular culture. Some of the older women who commented on my tweet also made that connection, drawing comparisons with 1970s British favourites like the Carry On films and the Benny Hill Show. One recalled a piece of health messaging that makes Influential’s effort seem almost tasteful: when she had her first child in 1979, there was a poster in the maternity ward promoting breastfeeding with the message “Breast is best, and Dad can suck on the empties”.

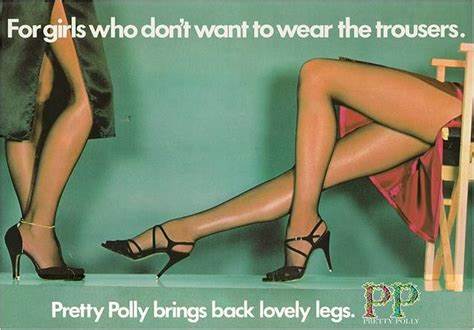

Commercial advertisers in this period often used wordplay that gave their ads a sexist/misogynist subtext. Below, for instance, is an ad for the UK hosiery brand Pretty Polly in which a sexualized image of women’s legs is given a witty caption–“for girls who don’t want to wear the trousers”–that has both an innocuous reading (“for women who prefer wearing skirts”) and a sexist one (“for women who want to be dominated by men”) which is also a dig at feminists, with their presumed desire both to dominate men and to look like them. Influential’s installation is very obviously in this tradition: it uses the same combination of visual imagery (disembodied legs/high-heeled shoes) and verbal innuendo.

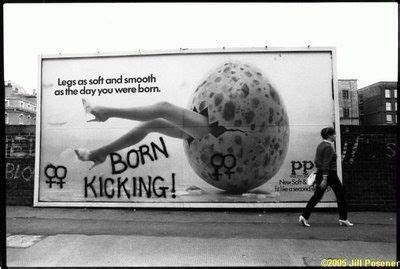

Back in the day, this kind of thing certainly grabbed feminists’ attention: it inspired complaints to the Advertising Standards Agency, stickering campaigns on the London Underground (“this advert degrades women”) and illegal spray painting of graffiti on street hoardings (Pretty Polly was one target for this form of activism, as seen below).

It may be because I’m old enough to remember this that the “don’t keep ‘em crossed” campaign makes me so angry. How did we get to the point where women designing a women’s health campaign in 2023 can reinvent the wheel of 1970s sexism without apparently seeing a problem? Even if they were genuinely unaware of the connection between uncrossed legs and rape, why did they think a cancer prevention campaign needed to be, above all, “playful” and “cheeky”? Why is it still assumed that you can’t get women’s attention by addressing them as serious human beings?

If you did want to take a more serious approach, one thing you’d need to do would be to think seriously about the reasons why many women are reluctant to be screened. Both in this campaign and in myGP’s earlier cat-themed effort, the key problem is assumed to be embarrassment, and the solution is to joke women out of it. But while embarrassment may be a factor, it’s certainly not the only problem. As many women who commented on Twitter observed, for a non-negligible subset of women the smear test is particularly daunting because of its potential to trigger memories of sexual assault and/or traumatic experiences giving birth. Women who avoid screening for trauma-related reasons are hardly going to be receptive to the “cheeky banter” approach.

Another thing that makes women hesitant is their knowledge that screening is often painful. Some Twitter commenters recalled occasions when they had said they were in pain and been ignored or told it was their own fault for not “relaxing” (the “uptightness” problem again). One woman healthcare professional who had been on both ends of the speculum described that instrument as “grim and bitey”, and wondered why more resources had not been devoted to improving its design, which has barely altered since it was invented.

In this particular case women may not have to endure the pain for much longer. Almost all cervical cancer is caused by the Human Papilloma Virus (HPV), and since a vaccine against HPV became available the case-rate among women young enough to have been offered it has dropped dramatically. Recently the NHS announced that it hopes to eradicate the disease by 2040. Which will, if it happens, be very good news. But it will not solve the larger problem, which is the longstanding tendency, now well-documented by research, for medicine to take women’s pain less seriously than men’s.

Hysteroscopy, for instance, a procedure used to investigate symptoms that could indicate uterine cancer, is typically performed in NHS clinics without pain relief (other than the over-the-counter painkillers women are advised to take beforehand), though it is so painful that it is not uncommon to have to abandon the procedure midway through. Colonoscopy, by contrast, a comparable investigative procedure which is also performed on men, is usually done under sedation.

It isn’t only women’s pain that gets dismissed as trivial. NICE, the body which approves NHS treatments, recently issued guidance suggesting that women experiencing menopausal symptoms like insomnia, mood swings and brain fog should be offered cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT). So, either they think the problem is in women’s minds, or else they think women should be satisfied with a treatment that helps them cope with their symptoms as opposed to one (HRT) that relieves them by targeting the cause. As one woman asked, will they also be recommending that older men with erectile dysfunction should be offered CBT rather than Viagra?

This systemic sexism is the larger context in which health messaging for women needs to be seen. The problem with campaigns like “don’t keep ‘em crossed” isn’t just their crassness: even if the form of the message were less offensive, if its content still boils down to “stop being a prude and get a smear test” then it will still be treating women who avoid screening like irresponsible silly girls, while ignoring the evidence that many are deterred by their prior experiences of being patronized, insulted, dismissed or blamed.

That said, there’s no getting away from the crassness—and that part of the problem could easily be fixed if the producers and commissioners of health messaging for women simply decided to stop using sexualized language and imagery. It isn’t just feminists, or women over 50, who find this inappropriate and offputting. Women may also object to it for religious or moral reasons, or because they find its humour tasteless, or just because they don’t see how it’s relevant. In Canada, some women criticized the 2016 “ladyballs” campaign for insulting their intelligence; one wondered if a campaign about testicular cancer would refer to men’s testicles as “brovaries”. Yet the marketing and PR professionals remain convinced that their “provocative” and “cheeky” approach is the right one. Why are they so wedded to the idea of sexing up cancer? Do they really know their audience, and do they actually care what it thinks?

In that connection I find it interesting that Karen Swan’s comment, quoted above, begins with the words “we wanted a campaign that…”. By “we”, presumably, she meant the creative team at Influential. And what agencies like Influential want from a campaign isn’t always what’s most effective for the target audience. Of course they have to pay attention to the client’s brief (if they didn’t they’d find it hard to stay in business), but they also want their campaigns to be noticed and evaluated positively by their peers. And for that purpose, being provocative has its advantages: a campaign that generates controversy is also one that gets attention.

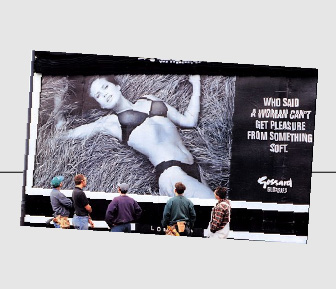

This strategy was famously used in the so-called “bra-wars” of the 1990s, when rival bra manufacturers and their advertising agencies competed to produce more and more “daring” ads. First we had the Wonderbra “Hello, boys” campaign, which put supermodel Eva Herzigova’s breasts almost literally in the viewer’s face: the giant billboard version even prompted fears that it would cause traffic accidents by distracting male drivers. Then came Gossard’s even more provocative depiction of an underwear-clad model reclining in what appears to be a haystack over the line “Who said a woman can’t get pleasure from something soft?”. This thinly-veiled allusion to erect penises attracted so many complaints that Gossard was forced to switch to “when a firework is smouldering, stand well back”.

This change in language was forced on Gossard by the Advertising Standards Authority (ASA), the body which regulates print and billboard advertising in Britain, and which adjudicates complaints about it from the public. But overall, their response to complaints about the bra-wars ads was surprisingly restrained. Gossard was only required to remove the “something soft” reference, while complaints about “Hello, boys” were dismissed altogether. The ASA’s adjudication said that “the copy lines invest [the model] with a particular personality and sense of humour”–or in other words, “Hello, boys” was not offensive and dehumanizing, it was just “playful and a bit cheeky”.

By contrast, a couple of ads which took a similarly playful and cheeky approach to men’s underpants, using close-ups of the model’s crotch area alongside jokey captions like “Loin King” and “Full Metal Packet”, were judged to have breached the ASA’s rules about “taste and decency”. Women’s breasts might be a legitimate subject for cheeky humour, but men’s penises were no laughing matter. Asked about this apparent double standard, an ASA spokesperson said: “The Authority reacts to prevailing standards. To some extent we live in a sexist society, and to some extent we reflect that”.

But by the mid-1990s it had also become possible for the makers of sexist ads to deploy a different argument, one that wasn’t about humour or playfulness–that using sexualized images of female bodies to sell products was not, as 1970s feminists had argued, degrading to women, but on the contrary, empowering. The women in the ads were not mere objects, they were agents; far from displaying submissiveness, they were making a statement about the power of female sexuality. The bra-wars ads might look to the uninitiated like 1970s sexism on steroids, but in fact what they represented was an “edgier”, more modern form of feminism. If you couldn’t see that a supermodel in a Wonderbra was the ultimate symbol of female empowerment, that was probably because you were a middle-aged, pearl-clutching prude.

This line went down well with the art-school/cultural studies crowd, and “Hello, boys”, in particular, is still remembered as “iconic” and “groundbreaking”. But that assessment overlooks an interesting if less well-known postscript to the bra-wars story. Both the UK companies involved, Gossard and Playtex (the makers of the Wonderbra), changed their marketing approach dramatically after realizing that the “iconic” bra-wars campaigns had done more to enhance the ad agencies’ prestige than to increase sales of the product being advertised.

In 1996, when Playtex announced that a new campaign for their Affinity range would feature the “elegant” but “accessible and clean-cut” Helena Christensen, the company’s account director at Saatchi and Saatchi explicitly related this change of direction to the controversy around Gossard’s “something soft” ad, saying “we don’t want to offend or upset women, which I think these ad campaigns do.” When a woman later became marketing director at Gossard, one of her first actions was to sack the agency that had created “something soft”, explaining, “I want to advertise to women, not men”. Even if they weren’t offended, market research showed that women were unimpressed by sexy poses and suggestive straplines. What they most wanted from a bra ad was “a good representation of what the actual bra looks like”.

Though this backlash against hypersexualized, controversy-courting bra ads was described in one report I read as a return to “the ethos of a bygone age”, in reality it was more like a return to the basic principles of marketing: if your aim is to sell more bras you should design your advertising for the people who actually buy bras. And that principle also applies to women’s health campaigns. To the professionals who design them it may seem obvious that effective advertising is “provocative” or “edgy”, and that sexualized imagery is “empowering”: those ideas are simply the water today’s creatives swim in. But if the reception of “don’t keep ‘em crossed” shows us anything, it surely shows it’s time to pull the plug.

Many thanks to everyone who commented on my Twitter thread