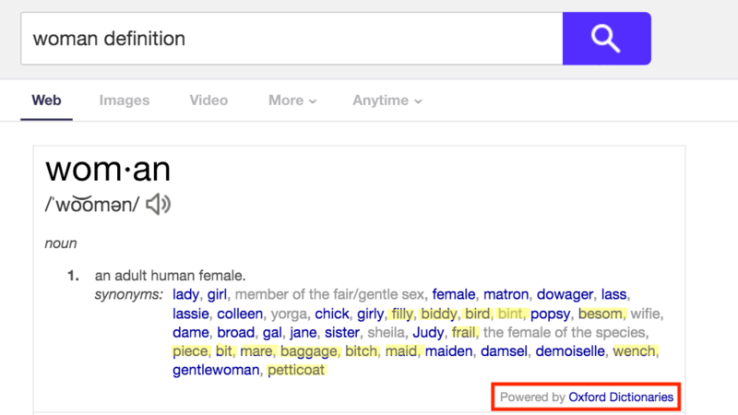

This week the Guardian writer Emine Saner drew my attention to a petition on Change.org asking Oxford University Press, the publisher of the Oxford Dictionary, to change its entry for the word ‘woman’.

The petition condemns this entry as ‘unacceptable in today’s society’, noting that many of the synonyms it gives for ‘woman’ are derogatory, and the illustrative examples are variations on old sexist themes:

A ‘woman’ is subordinate to men. Example: ‘male fisherfolk who take their catch home for the little woman to gut’, ‘one of his sophisticated London women’.

A ‘woman’ is a sex object. Many definitions are about sex. Example: ‘Ms September will embody the professional, intelligent yet sexy career woman’, ‘If that does not work, they can become women of the streets.’

‘Woman’ is not equal to ‘man’. The definition of ‘man’ is much more exhaustive than that of ‘woman’. Example: Oxford Dictionary’s definition for ‘man’ includes 25 ‘phrases’ (examples), ‘woman’ includes only 5 ‘phrases’ (examples).

The creator of the petition, Maria Beatrice Giovanardi, has found that Oxford’s entry is not an isolated case. In a piece entitled ‘Have you ever Googled “woman”?’ she examines the entries in several widely-used dictionaries and points out similar problems with all of them. Her petition targets Oxford, however, because as well as being, in her view, the worst offender, it’s also got a market advantage: it’s the dictionary you get with Apple’s products and the one that pops up first in searches on Google, Yahoo and Bing. Her petition calls on the Press

- To eliminate all phrases and definitions that discriminate against and patronise women and/or connote men’s ownership of women;

- to enlarge the definition of ‘woman’ and equal it to the definition of ‘man’;

- to include examples representative of minorities, for example, a transgender woman, a lesbian woman, etc.

As I told Emine Saner (whose own piece you can read here), I’ve got mixed feelings about this campaign. I do think the entries Giovanardi reproduces are terrible, and I’ll come back to that later on. But the petition is based on ideas about dictionaries–how they’re made, what they aim to do, and how they’re used–which, to my mind, are also a problem. I’ve written about this before, but let’s just recap.

Modern dictionaries are descriptive: their purpose isn’t to tell people how words should be used, but rather to record how words actually are used by members of the relevant language community (or more exactly, in most cases, by ‘educated’ users of the standard written language). What’s in the Oxford Dictionary entry for ‘woman’ does not represent, as Giovanardi puts it, ‘what Oxford University Press thinks of women’. The dictionary is essentially a record of what the lexicographers have found out by analysing a large (nowadays, extremely large—we’re talking billions of words) corpus of authentic English texts, produced by many different writers over time.

I’m not trying to suggest that dictionaries compiled in this way are beyond criticism: they’re not, and that’s another point I’ll come back to. But a distinction needs to be made between the producers’ own biases and biases which are present in the source material they use as evidence. A lot of the sexism Giovanardi complains about is in the second category: it’s the result of recording patterns of usage that have evolved, and still persist, in a historically male-dominated and sexist culture.

For instance, one reason why the Oxford entry for ‘man’ is longer than the one for ‘woman’ is that men have been (and still are) treated as the human default. Men are both people and male people; women are only women. The historical reality of sexism also makes itself felt in the presence of so many degrading and dehumanizing terms on lists of synonyms for ‘woman’. These reflect the social fact that women have been sexually objectified in ways that men have not; they have also been treated, in life as well as language, as men’s appendages or possessions. It’s not even two centuries since that was their status in English law.

If the vocabulary of a language reflects its users’ cultural beliefs and preoccupations, then it’s no surprise that many English words and expressions denoting women highlight their dependence on and inferiority to men, their physical appearance and their sexual availability. (In an early feminist study of this phenomenon, the linguist Julia Penelope Stanley identified over 200 words for ‘woman’ that meant, or had come to mean, ‘prostitute’.) It’s true dictionaries have a bias towards the usage of men from the most privileged social classes–the section of society that has historically had most access to the means of representation–but in this case it’s not obvious that a more balanced sample would paint a totally different picture. Sexism and misogyny have never been confined to a single class, or indeed a single sex.

The demand to eliminate ‘phrases and definitions that discriminate against or patronise women’ (or other subordinated groups: there have been similar campaigns in the past relating to entries where the issue was race, ethnicity or faith) implies that dictionaries should sanitise the reality of word-usage which is sexist, racist, anti-semitic or whatever, in the hope that this gesture will help to make a better world. Lexicographers tend to be wary of that suggestion, since it goes against their descriptivist principles. They also reject the popular belief that merely by including a certain word or definition they’re somehow endorsing it, giving it a degree of currency and acceptability which it would lack if it were not in the dictionary.

But while I agree this belief misunderstands the aims and methods of modern lexicography, I also think there’s something disingenuous about the standard ‘don’t shoot the messenger’ response. If the public at large treat dictionaries as arbiters of usage, then in practice, whether their producers like it or not, they do have authority, and therefore some responsibility to reflect on how it should be used.

In some areas it’s clear they have reflected, and concluded that some sanitising is justified. You may have noticed, for example, that Oxford’s entry for ‘woman’ doesn’t propose ‘cunt’ as a synonym: that can’t be because it isn’t used as one, so presumably it’s been excluded on the grounds of its offensiveness. In recent years there’s also been a move to eliminate the casual racism and homophobia which were features of some older dictionary entries (today you’ll find fewer references to ‘savages’ or ‘unnatural acts’). Casual sexism, by contrast, has mostly escaped the cull. I may not agree with Giovanardi’s proposed solution, but I think she’s right to raise this as a problem.

What solution would I be in favour of, then? Essentially, a more context-sensitive, ‘horses for courses’ approach. Different kinds of dictionaries serve different purposes and audiences: there are some cases where I think it would be wrong to sanitise the facts of usage, and others where nothing important would be lost by being a bit more selective.

The Oxford English Dictionary (OED)—the massive historical dictionary which is Oxford’s flagship product—contains an entry for ‘woman’ which is an absolute horror-show of sexism: the senses listed include things like

3a. In plural. Women considered collectively in respect of their sexuality, esp. as a means of sexual gratification.

4. Frequently with preceding possessive adjective. A female slave or servant; a maid; esp. a lady’s maid or personal attendant (now chiefly hist.). In later use more generally: a female employee; esp. a woman who is employed to do domestic work.

Further down there’s a long list of delightful idioms containing ‘woman’ (‘woman of the night’, ‘woman of the streets’, ‘woman of easy virtue’) and a section full of even more delightful proverbs and sayings (‘a woman, a dog and a walnut tree/ the more you beat them the better they be’). And many of the illustrative examples, even some of the most recent ones (this entry was last updated in 2011), are as terrible as you’d expect. Any feminist who reads the entry from beginning to end will want to go out and burn the world down. But in this case I believe that’s as it should be. The OED is designed primarily for scholars, and it’s an invaluable repository of cultural as well as linguistic history. Hideous though the ‘woman’ entry is, cleaning it up would do feminism a disservice: it would erase evidence that needs to be preserved for our own and future generations.

The Oxford Dictionary, however, as accessed via iPhones and search engines, is (or should be) a completely different animal. I said earlier that I thought the entry reproduced in Giovanardi’s petition was terrible, and what I meant by that was not only that it’s terribly sexist, but also that it seems poorly designed to meet the needs of those who use this type of dictionary. The basic definition of ‘woman’ is unremarkable (albeit redundant, since this is a high-frequency word that English-speakers generally acquire before they can read), but the thesaurus section is stuffed with archaic terms which would hardly be usable in any contemporary context. Who, in 2019, calls women ‘besoms’, ‘petticoats’ or ‘fillies’? And if you did encounter one of these expressions in a novel or period drama, the context would make clear what it meant. So what is this list of synonyms good for? What pay-off would its makers cite to justify its rank misogyny?

But in any case, does anyone in real life use their phone, or Google, to look up common words like ‘woman’? After speaking to Emine Saner, I rather belatedly began to wonder what people do use dictionary apps for, and I put out a call on Twitter asking people to tell me if they used them, what they did with them, and what the last word they’d looked up was. Leaving aside the people who replied that they only ever used either bilingual dictionaries or monolingual dictionaries for languages they weren’t native speakers of, the responses clustered in three main categories. In order of frequency, these were

- Checking the meaning and/or spelling of low-frequency words (examples included ‘obviate’, ‘noctilucent’ and ‘eschatology’)

- Using the thesaurus element of an entry—or an actual thesaurus app—to find synonyms to use when writing

- Searching for words while engaged in word-based leisure activities like doing crosswords or playing Scrabble.

One or two people mentioned other uses, like checking the pronunciation of a word they’d only ever met in writing, or looking into the history of a word, or decoding the slang terms used by their children (for this purpose Urban Dictionary was the go-to source). But no one reported looking up basic vocabulary items whose meaning, spelling and pronunciation they already knew. Of course you can’t draw general conclusions from what you’re told by a self-selected sample of your Twitter followers, but it seems possible the Oxford Dictionary entry for ‘woman’ isn’t exerting a malign influence on our attitudes to women, simply because so few of us will ever look at it.

I’m not saying that makes it OK to leave the entry as it is: I do think the dictionary makers should revisit their synonyms and illustrative examples (they could start by getting rid of any expression that no one under the age of 85 has ever uttered). But if I had to make them a to-do list, revising their ‘woman’ entry wouldn’t be at the top. Dictionaries reinforce sexism and gender stereotyping in other ways, which are arguably more pernicious because they’re not so immediately obvious.

An example is the persistent use of sex-stereotyped illustrative examples in entries for words that have nothing to do with sex or gender. I discussed this form of banal sexism in a previous post, prompted by the row that broke out when the anthropologist Michael Oman-Reagan queried the use of ‘a rabid feminist’ in the Oxford Dictionary entry for ‘rabid’. We’ve also got dictionaries for learners of English in which men mop their brows while charwomen mop the floor, and men slip on their shoes while women slip off their dresses. How do these sexist clichés enhance anyone’s understanding of the words ‘slip’ and ‘mop’? Do the entry writers think learners are planning to practise their English on a coach tour of the 1950s?

As I’ve said before, though, my feelings about political activists lobbying dictionaries are mixed: I can see why you might want to put pressure on what are, whether they acknowledge it or not, influential cultural and linguistic institutions, but something that bothers me about this approach (that is, apart from the problems I’ve already mentioned) is its linguistic authoritarianism. It’s buying into the idea that dictionaries can and should lay down the law—that it’s fine for them to prescribe, so long as what they prescribe reflects our own preferences rather than those of our political opponents. I know I’ve used this example before, but let’s not forget that Christian conservatives lobbied dictionaries in an attempt to stop them changing their entries for ‘marriage’ to include the same-sex variety–and progressives applauded when the dictionaries took no notice. In that instance feminists were happy to endorse the principle that dictionaries just record the facts of usage. I don’t think we can reasonably demand that they should be descriptive when it suits us and prescriptive when it doesn’t.

But the deeper problem underlying these contradictory demands is the status we accord to ‘the dictionary’ as the ultimate authority on language. In the past that was something feminists questioned: they were less interested in harnessing the power of what Mary Daly called the ‘dick-tionary’, and more interested in challenging its patriarchal claims to ‘authoritative’ and ‘objective’ knowledge.

During the 1970s, 80s and 90s, a number of feminists produced alternative dictionaries that embodied this challenge in both their content and their form. The compilers of these texts didn’t deny that their selection of headwords, definitions and examples represented a non-neutral point of view; rather they maintained that this was covertly true of all dictionaries (Cheris Kramarae and Paula Treichler’s A Feminist Dictionary defined a dictionary as ‘a word book. Somebody’s words in somebody’s book’.) Their entries emphasised the variability of meaning—words can mean different things for different speakers—and the fact that it’s contested rather than consensual. Though admittedly they were not much use if what you needed was a definition of ‘noctilucent’.

In some ways, as Lindsay Rose Russell points out in her recent history of women’s contributions to dictionary-making, these late 20th century feminist dictionaries anticipated digital-era efforts to democratise and diversify knowledge, as exemplified by Wikipedia and Wiktionary, and (in a different way) Urban Dictionary. They were anarchic, utopian, and they often featured a multiplicity of voices which they made no attempt to homogenise. They used sources that conventional dictionaries neglected, and tried to amplify the voices those dictionaries had marginalised or muted.

In theory the digital revolution offered an opportunity to develop this tradition further, and perhaps to produce feminist alternatives to the mainstream online dictionaries which most people use today. But in practice that hasn’t happened. Digital knowledge-making communities have been dominated by men, and they can be hostile environments for women—witness the many female Wikipedians who say they’ve been bullied or sidelined by men who treat the site as their turf. Any attempt to create a feminist dictionary online would be a magnet for these mal(e)contents, who would either want to take it over or to take it down. Ironically, there may be less space for feminist lexicography in the limitless expanse of cyberspace than there was in the olden days when dictionaries were books.

But although I regret the fading of the more radical spirit that animated projects like A Feminist Dictionary, I’m not completely opposed to the reformist approach. As Lindsay Rose Russell told Emine Saner, ‘we ought to care what definitions are made most readily available and why’–and we have every right to bring our concerns to the attention of the people responsible for those definitions. Even if Oxford’s public response is defensive or dismissive, I suspect that Maria Beatrice Giovanardi’s petition might still prompt discussion behind the scenes. Its demands won’t be met in full: a descriptive dictionary can’t eliminate all sexism from the record of a language in which sexism is so pervasive. But if it makes the producers aware that a lot of people find their entries for ‘woman’ gratuitously offensive, outdated and useless, they may, eventually, make some changes.* In this case I think they should, and I hope they will.

*since this post was written, the dictionary makers at Oxford have confirmed that they are reviewing their products with a view to getting rid of unnecessary bias in definitions and examples. They also plan to mark derogatory terms more clearly as such–though if those terms are in widespread use they will continue to appear in entries.